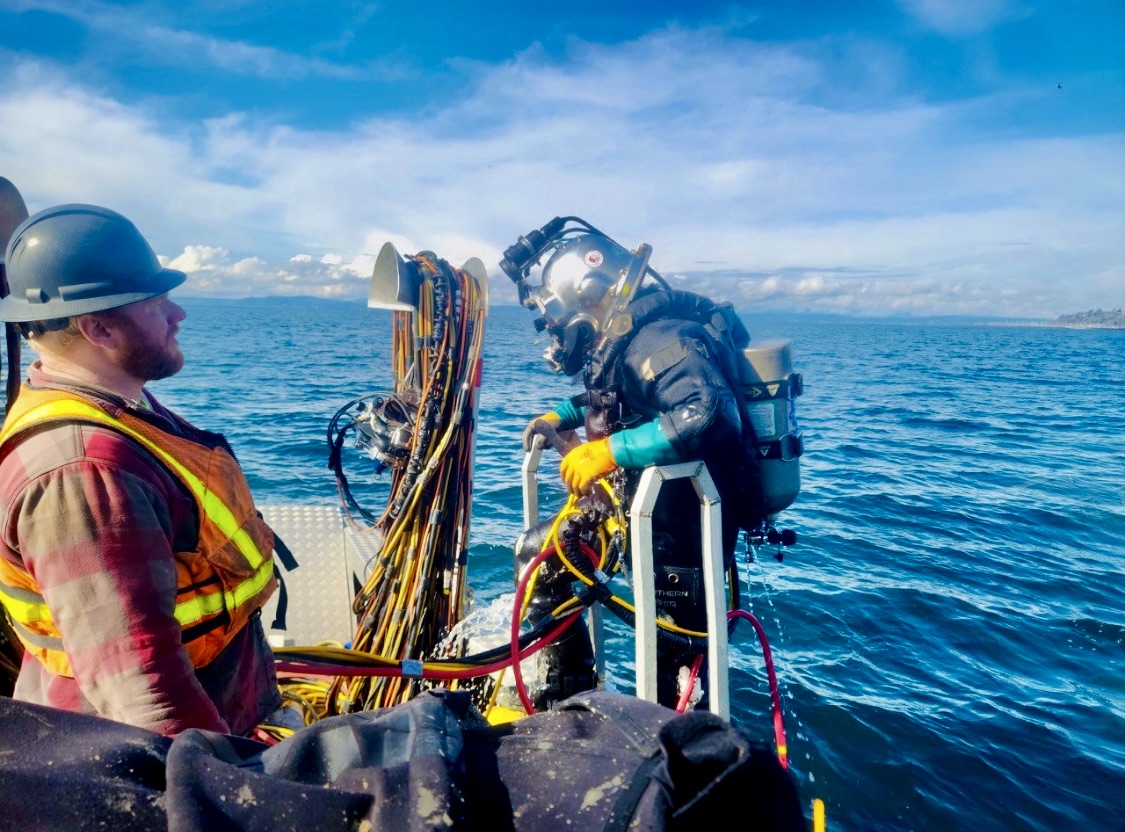

DEAN J. KOEPFLER | THE NEWS TRIBUNE

Commercial diver Kerry Donohue rides a tugboat to the eastern caisson – or foundation – of the new Tacoma Narrows bridge. Donohue, vice president of Associated Underwater Services of Spokane, is one of 16 divers working on the bridge. They are removing roofs from 30 airtight chambers at the caisson’s base.

Just hearing about Kerry Donohue’s job is enough to make some people queasy.

He’s a commercial construction diver, working at the bottom of the two foundations of the new Tacoma Narrows bridge. He works alone, inside spaces that are a lot like elevator shafts, with 15 stories of concrete and salt water above him. At that depth, no natural light penetrates. The only illumination comes from his headlamp.

Donohue, a big, good-natured Canadian with prematurely gray hair, seems surprised to hear his job gives people the creeps. He and the 15 other divers on the Narrows job are having the time of their lives, he said.”For us, this is luxury,” Donohue said. “We’re just stylin’ down there.”

For the past five weeks, the divers have used cutting torches to remove the steel roofs from the 30 airtight chambers at the bottoms of the tower foundations, or “caissons,” so cranes can dig beneath them. The air chambers measure about 20 feet on each side. From a commercial diver’s point of view, Donohue says, that barely even qualifies as an enclosed space.

“When you work inside a 36-inch pipe, now that can seem a little tight. “Donohue, 46, is the vice president of Associated Underwater Services Inc., a Spokane company subcontracted by the prime bridge builder, Tacoma Narrows Constructors. Associated Underwater Services has had divers on the bridge job since last March, when caisson construction began at the Port of Tacoma.

When anchors were being attached to the massive structures, 20 divers were on the job at once. Currently, 16 divers are working on the air dome removal, Donohue said. After the divers finish cutting out the air domes, they will help remove the caisson anchor attachments. Their jobs on the bridge will end when the caissons are finished this summer.

Most of the divers are from Washington and Oregon, Donohue said, but a few come from as far away as California and Arizona. Donohue and the other divers have seen their share of tight spots.

They’re seasoned pros, most between 35 and 50, and many have dived together all over the world, from Trinidad to the Arctic, working in gas fields, on oil rigs and countless dams. For creepiness, Donohue says, the bridge caissons are nothing compared to cleaning up the 1982 Ocean Ranger oil platform disaster in Newfoundland, with the bodies of 84 men lying on the ocean floor around him. Or to a job in Trinidad, where he accidentally smashed his finger and watched the blood diffuse into a swarm of circling sharks. Diving in the Narrows has its own dangers, Donohue admits, but more can go wrong outside the caissons than inside. Diving outside the caissons is possible only during the brief “slack” periods, usually about 20 minutes, between incoming and outgoing tides. Otherwise, the currents race back and forth through the channel like a river in flood stage, creating treacherous whirlpools. Inside the caissons, there’s no worry about currents, but there are other concerns, Donohue said. Gases from the cutting torches can accumulate in hidden air pockets and suddenly explode. There’s a constant danger of being crushed by falling objects. Pressure differences between the air chambers and the shafts above them could suck divers into holes or blow them to the surface at a speed that would burst their eyeballs. As always, working at depths between 130 and 150 feet carries the constant danger of the “bends,” a sometimes fatal condition caused by surfacing too quickly.

“In diving, you don’t make too many mistakes,” Donohue said.

The divers are paid well for the chances they take. Their hourly wage starts at $80 an hour, more than any bridge workers. But Donohue points out they are paid that rate only when they’re diving or in the decompression chamber, not when they’re in support roles on the surface. The dangers of diving are heightened by the consequences of what divers call “Martini’s Law” – that is, for every 50 feet of depth, a diver experiences roughly the anesthetic equivalent of one martini. The feeling, caused by breathing compressed nitrogen, is characterized by slowed mental activity and euphoria. At the three-martini level, where the bridge divers are working, it’s easy to blissfully forget what you’re doing, Donohue says. But the diving teams are organized to make accidents hard to occur, he says. The divers work in two six-man teams, both working a 10-hour shift each day.

All team members are divers, and during their shift they cycle through all the jobs, including diving and sitting in the decompression chamber. When one diver is in the shaft, most of the others are concentrating on his safety. One man is glued to a live video feed transmitted from a camera on the diver’s helmet. He keeps the diver on track, occasionally reminding him why he’s down there and where his tools are.

“You’ve got five guys looking out for you,” Donohue said. “How often in your life do you get that?”

To avoid the bends, the divers must surface slowly. When their 45 to 70 minutes of bottom time is up, they climb in a cage called a “man basket,” and a winch operator hoists them up, pausing every 10 feet to allow their bodies to readjust to the reduced pressure. The trip from bottom to top takes 27 minutes. When a diver surfaces, he has just 3 1/2 minutes to scramble out of his suit and into inside the decompression chamber set up on top of the caisson. Modern diving equipment has made working underwater relatively comfortable, he said. Instead of the old “dry suits,” which keep a layer of air around the divers, Donohue and the others on his team wear hot-water suits, which circulate 108-degree water inside.

“It’s like working inside a shower,” he said.

With all the risks, why does he keep diving?

“By the time I figured out how dumb I was, it was too late to change,” Donohue jokes.

When he’s serious, he says he loves the challenges and the unexpected.

For example: A few days ago, Donohue said, he heard one of his fellow divers, a usually taciturn Montanan named Chris Hackworthy, break into excited laughter on the radio, midway through his dive. “Watch this,” Hackworthy said, and held one of his cutting rods out in front of him. As the divers on top watched the video feed, a large tentacle unfurled across the screen, grasped the rod and pulled it away. The tentacle belonged to an octopus, Donohue said, one of the giant five-footers that live in the Narrows. The octopus took several more rods from the diver, Donohue said, as laborers from all over the caisson clustered around the screen to watch. Putting an effective diving team together takes more than just assembling good divers, Donohue said. A safe and efficient team takes a mix of talents and personalities.

“Being good in the water isn’t everything,” he said. “You’ve got to look at the whole picture. “If you have five prima donnas, they’re all talking about how good they are all the time and nothing gets done. They have to be good workers – steady, solid guys who are good at a lot of things, jacks of all trades.” The most important thing, though, he said, is dependability. “You trust these guys with your life every single day,” he said. Everything that’s good about diving is even better on the Narrows project, Donohue said.

“Everybody knows about Galloping Gertie,” he said. “The guys like to work on it just to say they work on the bridge.”

“And it makes good bar stories. The girls around here are crazy about divers.”

Rob Carson: 253-597-8693

rob.carson@mail.tribnet.com